Prime Minister Justin Trudeau: A Foreign Policy Assessment 2015-2019

Executive Summary

An internationalist and a progressive, Justin Trudeau consistently boosts diversity, social justice, environmentalism and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. A gifted retail politician, Trudeau prefers campaigning and contact with voters to the hurly-burly of the House of Commons. He possesses an empathy and emotional intelligence most people found lacking in his famous father, Pierre Trudeau. But are these attributes and causes out of sync with our turbulent times?

Mr. Trudeau is learning firsthand what British prime minister Harold MacMillan warned U.S. president John F. Kennedy what was most likely to blow governments off-course: “Events, dear boy, events.”

As Trudeau begins a second term as prime minister, the going is tougher. The Teflon is gone. He leads a minority government with new strains on national unity. Parliament, including his experiment in Senate reform, is going to require more of his time. Canada’s premiers will also need attention if he is to achieve progress on his domestic agenda. Does he have the patience and temperament for compromise and the art of the possible?

The global operating system is increasingly malign, with both the rules-based international order and freer trade breaking down. Managing relations with Donald Trump and Xi Jinping is difficult. Canadian farmers and business are suffering – collateral damage in the Sino-U.S. disputes.

In what was supposed to be a celebration of “Canada is back”, there is doubt that Canada will win a seat on the UN Security Council in June 2020. Losing would be traumatic for his government and their sense of Canada’s place in the world. It would also be a rude shock for Canadians’ self-image of themselves internationally.

Introduction

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau declared “Canada is back” and promised a return to “sunny ways” upon winning a majority in the October 2015 federal election. The son of Pierre Trudeau – Canada’s third-longest serving prime minister – had quickly climbed the greasy pole of politics. For the former drama teacher, “bliss was it in that dawn to be alive”. For his band of Gen Xers, especially those destined for cabinet office, “to be young was very heaven”. William Wordsworth captured the moment. For the temper of the times, however, Trudeau should have kept at hand a copy of Machiavelli’s The Prince.

Four-plus years and a second election later, Trudeau has had a sobering, often frustrating education in the art of governing. Hope and conviction met the realities of managing a cabinet chosen more for its look than experience, a caucus that wanted attention from its leader and not just his acolytes, and a public that is diverse and increasingly skeptical of politicians and governments. All of this was set against an international backdrop of populism, protectionism, rearmament and the breakdown of the rules-based liberal order.

Trudeau has pushed his personal priorities – climate, gender and reconciliation – while grappling with the permanent files that preoccupy all Canadian prime ministers – security, unity and Uncle Sam. As he begins a second term leading a minority government, the achievements are hard won and probably fewer than expected. The road ahead remains bumpy with more ashcans than roses.

Cabinet-making

The 2015 throne speech focused on four major priorities: the middle class, reconciliation, diversity and international engagement. In an unprecedented demonstration of transparency, ministers were all given public mandate letters detailing their objectives.

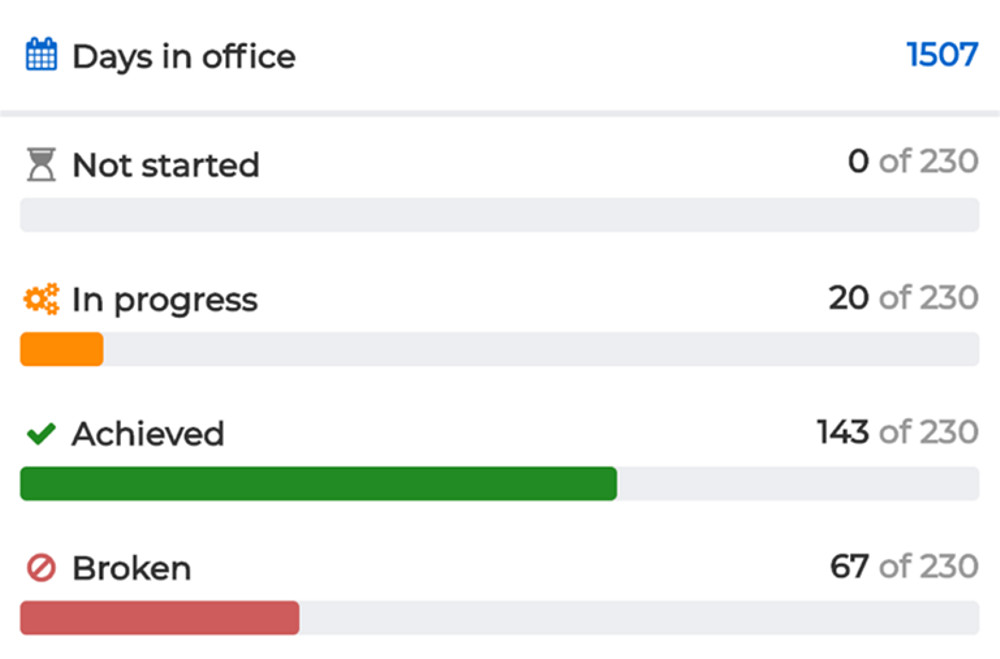

Even if his government’s foray into “deliverology” was mocked, the independent Trudeaumeter assesses 143 of 230 promises achieved, 67 broken – notably the promised reform of Canada’s first-past-the-post electoral system and failing to balance the budget by 2019 – and the rest in progress. Notably, during his first term the Trudeau government would decriminalize cannabis and legalize assisted suicide.

The 2019 throne speech identified five priorities that reflected strong continuity from those of 2015: fighting climate change; strengthening the middle class with its own minister, and more tangibly, a tax cut; walking the road of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples; keeping Canadians safe and healthy with new gun control, although pharmacare is less likely; and positioning Canada for success in an uncertain world.

In terms of foreign policy, the 2019 mandate letters to the ministers prioritized peace operations and the modernization of NORAD’s North Warning System; reaffirmed the Feminist International Assistance Policy; the creation of a Canadian Centre for Peace, Order, and Good Government; the conceptualization of a new cultural diplomacy strategy; the legislative passage of the new NAFTA; the creation of a Canada free trade tribunal; the modernization of the Safe Third Country Agreement with the U.S. and the new border enforcement strategy.

Gender, Diversity and Feminism

The original Trudeau cabinet reflected gender parity: 15 women and 15 men. Most were under 50, reflecting both generational change and Canadian diversity with two First Nations and three Sikh members. Only 10 cabinets around the world have gender parity, and the global average for women holding ministerial positions is around 18 per cent.

Speaking at a UN summit (2016) focusing on women, Trudeau promised to continue saying he is a feminist “until it is met with a shrug.” His government introduced “feminist” budgets with a gender equality statement, created a feminist international assistance policy, passed pay equity legislation and made women’s empowerment and gender equality key priorities of the 2018 G7 Charlevoix summit. While there has been the inevitable criticism around delivery, the policy is soundly rooted. As a McKinsey Global Institute study, The Power of Parity (2015), concluded, advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth. The Trudeau government’s policy built on work advancing maternal and child health that former prime minister Stephen Harper had personally led.

Reconciliation

As one of its first actions in 2016, Trudeau’s government signed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. When it comes to reconciliation with Canada’s First Nations, Trudeau said: “We have to be patient. We have to be present. We have to be unconditional in our support in a way a parent needs to be unconditional in their love – not that there is a parent-child dynamic here.”

Canadians, Trudeau argues, have spent decades advancing international goals on poverty and human rights, while failing their First Peoples. Reconciliation is, arguably, the unfinished business of colonialization. Whether this constitutes “ongoing genocide” – a conclusion of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (2019) – is debatable.

First Nations, including Métis and Inuit, account for almost five per cent of the Canadian population, with over half living in Canada’s western provinces. Since 2006, their numbers have grown by 42.5 per cent – more than four times the growth rate of the non-Indigenous population.

Is reconciliation working? In the words of Justice and now Senator Murray Sinclair, who headed the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission: “Education is what got us here and education is what will get us out.” The commission set out 94 calls to action and in its annual report card (2018), KAIROS, a joint-venture ecumenical program administered by the United Church of Canada, “acknowledges that significant progress has been made in the majority of territories and provinces.” But it will require more time, money and effort.

Ironically, despite his avowed feminism and focus on aboriginal reconciliation, Trudeau would suffer his biggest political setback when two of his most prominent cabinet members, Jody Wilson-Raybould, the first Indigenous Justice minister, and Treasury Board president Jane Philpott quit the cabinet. Trudeau’s principal secretary and friend, Gerald Butts, and his clerk and head of the Public Service, Michael Wernick, would also resign. Wilson-Raybould accused Trudeau and his office of pressing her to give preferential treatment to a Montreal-based engineering firm, SNC-Lavalin and, after the ethics commissioner contravened the Conflict of Interest Act, she sought an apology.

Would an apology from Trudeau have helped? If Pierre Trudeau was unapologetically without regrets, Justin Trudeau’s apologies are frequent, dramatic and sincere. Most of them are for the actions of previous governments dating back to the 19th century over their treatment of the Indigenous population or migrants. Autres temps, autre moeurs. A public opinion survey (July 2019) assessed that most Canadians thought “Justin Trudeau apologizes too much for government wrongdoing from the past.”

Pollsters identify the affair as lifting the Teflon that had once enveloped Trudeau. A plea bargain with a fine that allows SNC-Lavalin to still qualify for government work was reached in December 2019. Trudeau observed that: “there are things we could have, should have, would have done differently had we known, had we known all sorts of different aspects of it.”

Climate Change

Trudeau has consistently campaigned for climate change action and his government enthusiastically endorsed and signed the Paris Climate Accord. He declared: “With my signature, I give you our word that Canada’s efforts will not cease … Climate change will test our intelligence, our compassion and our will. But we are equal to that challenge.”

But for Canadians, managing climate is complicated. We are the fourth coldest country in the world after Kazakhstan, Russia and Greenland. We also have abundant quantities of energy sources – coal, oil, natural gas and uranium – that keep us warm during our long winters, and whose export pays the bills for universal health care and public education.

Environmentalists have focused on the pipelines that transport oil and gas, and as with most infrastructure projects, no one wants them in their backyard – the NIMBY problem. Alberta is the richest province in Canada, thanks to long-term investments in technological know-how that have freed its mineral wealth.

But Alberta is landlocked, so to get its oil and gas to market, it depends on pipelines. The Trudeau government cancelled the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline. Another proposed pipeline to Canada’s East Coast was cancelled in part because of opposition from governments in Ontario and Quebec, where Premier François Legault described it as “dirty oil”. Under some duress, the Trudeau government purchased, at considerable public expense from its American owners, the existing Trans Mountain pipeline into Vancouver and promised to complete the proposed twinning project after the conclusion of the court-required consultations, especially with the First Nations on whose lands it transits.

All of these actions, of course, strained national unity. Albertans protested that the equalization funds generated by their “dirty oil” made possible, for example, heavily subsidized day care in Quebec.

Their shared climate commitment and Canadian efforts that helped bring about the Paris Climate Accord originally cemented the bromance between former U.S. president Barack Obama and Trudeau. Obama likely saw in Trudeau a younger version of himself: liberal, multilateralist and committed to diversity and environmentalism.

Prime Ministers’ Permanent Files

Canadian prime ministers have three permanent files on their desks. The first, in common with every other leader, is to keep the nation secure and the economy prosperous.

The second is to preserve and sustain national unity, no easy task in a diverse country of 5½ time zones, two official languages and 634 First Nations with aspirations to self-government.

The third is managing the relationships with the rest of the world, chief among them the United States, our principal ally and pre-eminent trading partner.

Canada is prosperous and the economy is chugging along, although economists worry that this owes a lot to Donald Trump’s goosing the U.S. economy, oblivious of his country’s trillion-dollar deficit. When the reckoning comes due, how will Canada fare? Is the Trudeau government prepared?

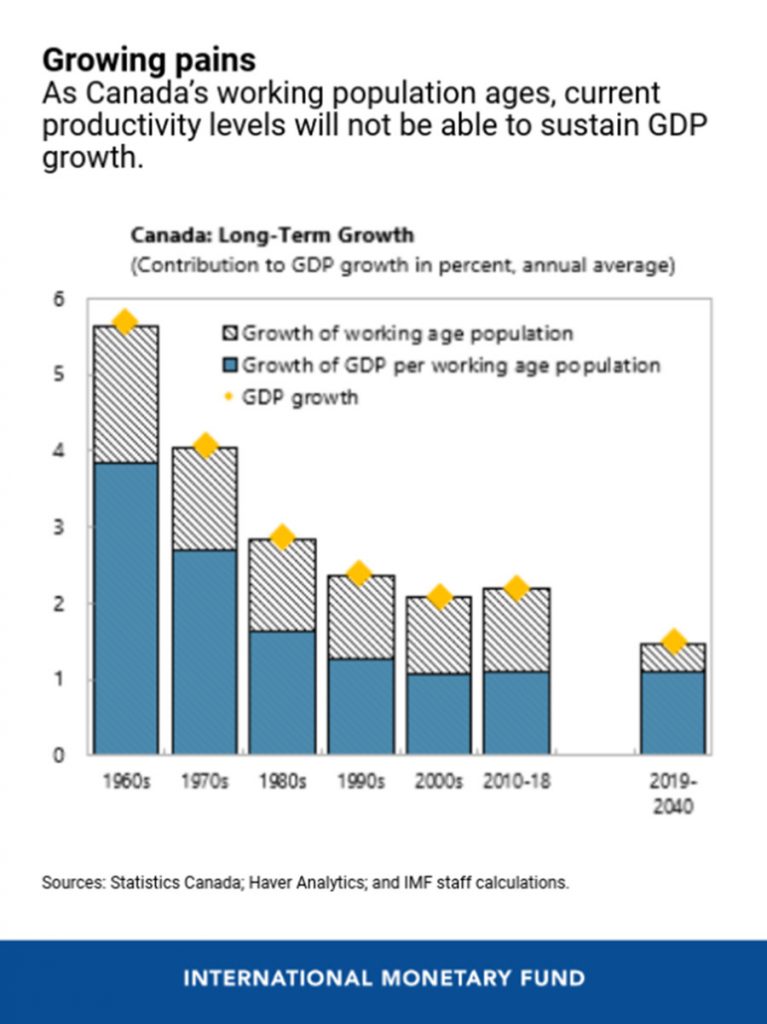

Trudeau can argue that his policies are growing the middle class. Critics argue that running chronic budget deficits is creating debt for the next generation. Redistribution will not address Canada’s weak productivity performance.

Since the Legatum Prosperity index began in 2007, Canada has held the consistent rank of eighth of 149 nations, following assessment of factors that include economic quality of life, business environment, governance, education, health, safety, security, personal freedom, social capital and natural environment.

The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) annual summary (2019) of Canada’s fiscal policy says Canada’s economy – and its management – is good, marked by “a judicious mix of policies” that support “inclusive growth and reduce vulnerabilities in the financial system”. The federal debt-to-GDP ratio, the lowest in the G7, is expected to decline to 29.1 per cent by 2024, representing its lowest level since 2008-2009. Growth is solid and business confidence is returning with the negotiation of the new NAFTA. Financial institutions are robust and taxation levels keep Canada competitive, although business argues for adjustments to regulatory barriers and openness to foreign investment.

Trade barriers between provinces remain the unfinished business of Confederation. Internal trade represents roughly 1/5 of Canada’s annual GDP. The Trudeau government has made some headway, including the 2017 Canadian Free Trade Agreement (CFTA) to resolve regulatory barriers and establish more efficient dispute settlement processes. Interprovincial barriers to trade in wine and beer have been eased, but 152 years on, there is still much work to be done.

Like most Western nations, Canada’s population is aging, which has implications for pensions and health care. Immigration partly alleviates this problem. Canada takes in about one per cent of its population annually – between 300,000 and 350,000 migrants. One of five residents in Canada was born outside the country. Most new migrants come from Asia – China, India and the Philippines. In our biggest city, Toronto, almost half the population was born outside of Canada. Our other big cities – Montreal, Vancouver and Calgary – also have a significant percentage of foreign-born residents.

Immigration is not the hot-button issue that it is in the United States but this reflects a smart selection policy. Canadians were generally proud of Trudeau’s pledge to take in 25,000 Syrian refugees (we eventually took in 60,000). The major parties in Canada support immigration with the emphasis on recruiting migrants with necessary skills. The reaction in Manitoba, Ontario and especially Quebec when U.S.-based refugee claimants crossed into Canada in response to Trump’s changes to U.S. immigration is a warning that public tolerance is not as liberal as Trudeau may think.

National Unity

Shortly after becoming leader, Trudeau threw out of caucus the Liberal senators appointed by his predecessors and vowed to appoint those drawn from an independent advisory body so as to create an independent chamber of sober second thought. Its reports, as with the recent study arguing that cultural diplomacy take front stage in our foreign policy, can become the basis for government action. As prime minister, he followed through and now most of the senators in the upper chamber owe their appointments to Trudeau. It is too soon to determine whether the experiment in having a membership that more closely resembles the Order of Canada has worked or whether it will endure. Senator Peter Harder, who stepped down after serving as government representative, endorses the new approach but observed that having appointees with legislative experience would be useful.

Having won seats in every province and territory in 2015 – no small accomplishment – Trudeau rightly claimed that he enjoyed broad national support.

That provincial governments soon began to shift from liberal to conservative probably says more about Canadians’ penchant for hedging and balancing between the levels of government. National problems are often resolved at first ministers meetings between the provincial premiers and the prime minister. There have been over 70 such meetings since 1945. Climate change was top of the agenda in Trudeau’s four meetings (2015, twice in 2016 with one that also included Indigenous leaders, and 2018). While the leaders acknowledged the climate problem, there was no consensus on how to manage it.

The Trudeau government imposed a carbon tax on provinces that failed to come up with commensurate carbon-reduction measures designed to help meet Canada’s commitment under the Paris Climate Accord. Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick and Ontario all became subject to a federal carbon price after refusing to create their own. While these provinces challenged the federal measure, the courts have ruled that climate change is a matter of “national concern” and Ontario’s chief justice wrote of “the need for a collective approach to [such] a matter”.

Unlike our southern neighbour, Canada has relatively strict gun control legislation that Trudeau promises to further tighten. Canada’s murder rate is closer to that of Europe than to the United States. While there is growing concern about the use of guns in Toronto, The Economist ranked Toronto the fourth safest major city in the world and the safest major city in North America.

National unity, always a challenge, is again strained. While it will never convince the Wexiters, getting the Trans Mountain pipeline built is important not just to get our oil to market but to underline that we can still do national projects in Canada. In Quebec, provincial legislation banning religious symbols defies Trudeau’s inclusiveness. The courts may fix this.

The one relationship that Canadian prime ministers have to get right, opined former prime minister Brian Mulroney, is the one with the American president. Mulroney’s relationship with Ronald Reagan netted the original Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement and acknowledgment of Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic. Mulroney’s equally close relationship with George H. W. Bush won the acid rain accord and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Trudeau understood this. It was easy with Obama. It is hard work with Trump.

The greatest test of Trudeau’s foreign policy management is handling Trump and the U.S. relationship. He avoided the easy route – become the anti-Trump – recommended by members of his cabinet, caucus, the punditry and Joe Biden. Instead, he and his team worked hard to establish an entrée into the Trump White House through various channels, including first daughter Ivanka and her husband, Jared Kushner. It worked. Trump likes celebrities and Trudeau and his wife, Sophie Grégoire Trudeau, possess the right celebrity aura.

The relationship was tested often, especially at the 2018 G7 summit in Charlevoix, Quebec, when Trump, who left early for his first meeting with Kim Jong-Un decided that host Trudeau had somehow offended him. Trump tweeted that Trudeau was “meek and mild … weak and dishonest” and withdrew the U.S. signature from the communiqué. Trudeau later said he took it all with a “grain of salt” and persevered.

Trudeau’s U.S. ambassador, David MacNaughton, was exactly right for the challenge. He quarterbacked a campaign to support Canadian interests, especially through the renegotiation of NAFTA, that focused on Trump’s base in the Midwest – all states whose main trading partner was Canada – as well as in Congress. Traditionally, protectionism and narrow interests emanating from Congress and the states are the source of Canadian headaches. But allies – in Congress, the statehouses, and governors and mayors who appreciate the importance of mutual trade to job creation – have become a counterweight to Trump’s unpredictability, recklessness and chaotic behaviour.

Trudeau’s Continuing Foreign Policy Vision

While marred by partisan shots at the Conservatives, Trudeau’s Montreal speech (August 2019), is the most thorough self-examination of his foreign policy as prime minister. Unabashedly internationalist, he re-commits to multilateralism – UN, NATO, G7, G20 – but acknowledges that we operate in a “more unpredictable and unstable world, where some have chosen to step away from the mantle of global leadership, even as others challenge the institutions and principles that have shaped the international order”. He reaffirms the importance of the U.S.’s relationship with Canada: “To say that the U.S. is our closest ally is an understatement. Canada has long benefited from this relationship, and from American leadership in the world. We are friends and partners more than mere allies. We share more than just a border – we share culture, food, music, business. We share a rich history, and we share many of the same core values.”

Without explicitly identifying Trump, Trudeau places responsibility for the current conditions on Trump’s decision to embrace America First. Trudeau points out that “protectionism is on the rise, and trade has become weaponized. Authoritarian leaders have been emboldened, leading to new forms of oppression. Calls for democratic reform, from Moscow to Caracas, are being suppressed. Crises that were once met with a firm international response are festering, becoming regional emergencies with global implications. And all of this is making it more difficult to solve the problems that demand urgent global action. Climate change is an existential threat to humanity, with science telling us we have just over a decade to find a solution for our planet. And technological change is happening at an unprecedented rate, transcending borders, re-shaping our societies, and leaving many people more anxious than ever.”

Trudeau makes the case for “free and fair trade”, pointing to the renegotiated NAFTA, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Comprehensive and Economic Trade Agreement (CETA). He argues for responsible reform of the World Trade Organization (WTO). He argues that in our “more unstable world, Canada must also be prepared to both defend ourselves and step up when called upon.” He also points to investment in defence and security, especially sea power and new fighter jets, saying, “we make the greatest contribution to global stability when we match what Canada does best to what the world needs most.” He recognizes China’s growing power, “but make no mistake: we will always defend Canadians and Canadian interests. We have a long history of dealing directly and successfully with larger partners. We do not escalate, but we also don’t back down.”

Acknowledging other challenges, Trudeau says: “White supremacy, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism are an increasing scourge around the world and at home. Gender equality is backsliding. Human rights are increasingly under threat. This is the world we’re in. And so we cannot lose sight of our core values. That means being prepared to speak up, and knowing that sometimes, doing so comes at a cost. But when the courage of our convictions demands it, so be it.” Looking forward, he says: “Canada should place democracy, human rights, international law and environmental protection at the very heart of foreign policy … As some step back from global leadership, we should work with others to mobilize international efforts, particularly by ensuring the most vulnerable and marginalized have access to the health and education they need. Canadians have found strength in diversity and benefited from openness. Financial strain should never hold Canadians back from exploring the world or building positive connections abroad …”

There are other speeches including his Davos speech on Canadian resourcefulness (January 2016) and his speech while he was still in opposition on North American relations (June 2015). Trudeau embraces multilateralism and a progressive agenda on trade and the environment. But the signature themes remain: climate, feminism and gender equality, and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

His UN General Assembly speeches were essentially one-plate affairs addressing migration (2016), then reconciliation (2017), with climate as a side dish for both. The Charlevoix G7 summit (2018) reflected his signature issues with a specific focus on topics like plastics in the ocean. He embraced the Christchurch Call to Action (May 2019) to eliminate terrorist and violent extremist content online.

A spontaneous sense of Trudeau’s global perspective is found in an interview he gave to CBC journalist Aaron Wherry in January 2019 for his book, Promise and Peril: Justin Trudeau in Power. Asked if the issues with China and Saudi Arabia stem from the U.S.’s failure to lead, Trudeau says: “obviously that’s a reflection of part of it … But having the Americans there to enforce Pax Americana around the globe over the past decades made it a little bit easier for all of us who have our lot in with the Americans. And I think what we’ve seen was that if the stability and the rules-based order we’ve built as a world relies entirely on one country continuing to behave in a very specific, particular way, then maybe the world’s not as resiliently rules-based as we think it is. And had it not been the particular circumstance we have right now, maybe it would’ve been something else. At one point you’ve got to decide – well, are you a world, are you countries, are you an international community that believes in those rules or not? And it shouldn’t be fear of punishment or consequences that keeps you behaving right.”

“I mean, the reason you and I don’t go murdering people is not because, ‘Well, it’s against the law.’ It’s because that’s where our values and where our beliefs are. So if we’re going to actually build a better world that is rules-based and solid and predictable, I think there was always going to be a moment where people have to sort of put up or shut up: either you’re standing for the rules even as it gets awkward and difficult and people are unhappy with you because you’re applying the rules. Or you don’t.”

“And I think this is something that we’re obviously going through as a world right now, and people are deciding how they want to position themselves. But I am very, very serene about Canada’s positioning in this and our history that leads us to this. But also our vision for the future that says, if we don’t follow rules and we accept that might is right in the international rules-based order, then nobody’s going to do very well in the coming decades.”

“As the Americans make different political decisions over the cycles, and even if the Americans do re-engage in a way, I think the lesson is that all of us need to be a little more rigorous in the way we stand for and expect and push back on others who are not following the rules that we abide by and accept. I think this is probably a moment that, again, in hindsight, fifty, a hundred years from now, we’ll say, ‘Yeah, this was a moment where people had to decide whether we do believe in an international rules-based order or not.’”

Then-Foreign Affairs minister Chrystia Freeland gave the government’s definitive foreign policy speech in 2017. It was erudite in its defence of liberal internationalism, robust collective security and the rules-based system, arguing that Canada is an “essential country” in that defence. She would champion the passage of Magnitsky legislation (2017) enabling Canada to sanction, impose travel bans on and hold accountable those responsible for gross human rights violations and significant corruption thus ensuring that “Canada’s foreign policy tool box is effective and fit for purpose in today’s international environment.” It has since been used to sanction individuals notably those from Venezuela, Myanmar, Russia, South Sudan and Saudi Arabia.

The Freeland speech was much more digestible than her predecessor Stéphane Dion’s “ethics of responsible conviction” remarks on foreign policy at the University of Ottawa (2015). But while Mr. Dion’s remarks were wonkish, they did make the sound observation that severing ties with governments we do not like is not effective diplomacy. In the case of Iran, that the Harper government declared a terrorist state in 2012, Dion observed that “severing of ties with Iran had no positive consequences for anyone: not for Canadians, not for the people of Iran, not for Israel, and not for global security.” Of Russia, Dion sensibly observed that as long as we refuse to engage Russia through diplomatic and political channels, we preclude any opportunity to advance shared interests in the Arctic or to support Ukraine through negotiations. Unfortunately, these sensible suggestions were not picked up by Ms. Freeland, who on Russia is shaped by anti-Communism (natural given her Ukrainian heritage and the fact the Russians declared her persona non grata in 2014).

Chrystia Freeland’s feistiness aggravated Trump, who labelled her a “nasty woman”. But she effectively worked her counterparts – first, Rex Tillerson, and later, Mike Pompeo – as well as Congress. Early on, as International Trade minister, she had charmed GOP Senate Agriculture chair Pat Roberts, and thus helped resolve the decade-long country-of-origin dispute. This dispute, essentially over access for Canadian and Mexican beef and pork, had also earned her the friendship of Mexico’s then-secretary of Economy, Ildefonso Guajardo, with whom she would work closely during the NAFTA renegotiations. Freeland played a key role in securing CETA with the European Union (2017) and the 2018 CPTPP.

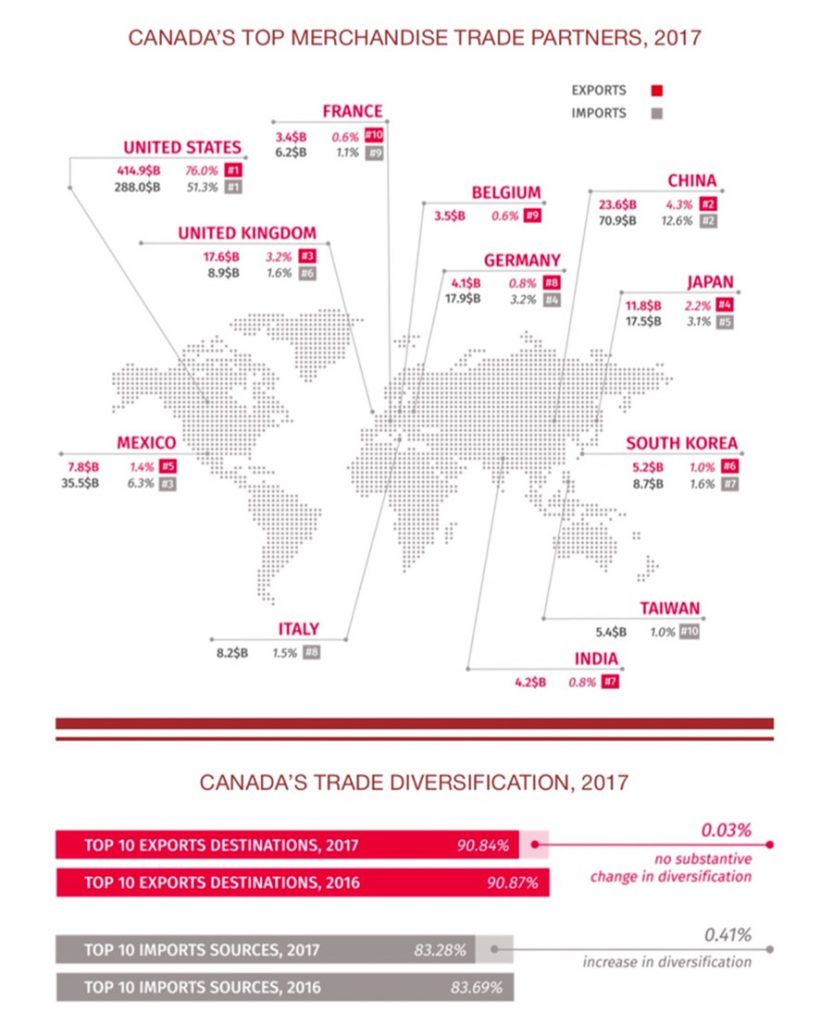

The CETA and CPTPP negotiations were inherited from the Harper government. While there remained some residual wariness about trade deals in his cabinet and caucus, Trudeau understood that our nation’s trading interest is best served by opening new markets and diversifying Canada’s trade dependence – 75 per cent of our exports – on the U.S.

Elements of the progressive trade agenda are reflected in CETA, CPTPP and the renegotiated North American free trade pact, as well as bilateral trade deals with Chile and Israel, but its limitations and the lesson of overreach became clear. China’s Premier Li Keqiang gave labour and Indigenous rights the back of his hand, and plans for a closer economic partnership with China never materialized. They are now on hold in the wake of the controversy involving Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou’s extradition, which has seen Canadians held hostage and our food exports curtailed.

There was too much virtue-signalling. Relations with China, Russia and Saudi Arabia are in the deep freeze. Relations with Asian nations still need a strategy and more engagement. The magical mystery tour to India chilled relations, not because of Trudeau’s dress, but on security issues with Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Wobbliness at the Da Nang APEC summit on CPTPP negotiations annoyed fellow leaders. Relations with Japan’s Shinzo Abe were patched up with closer defence co-operation. Despite his geniality, Trudeau’s close fellow-leader relationships are few: Irish Taoiseach Leo Varadkar, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, and perhaps France’s Emmanuel Macron.

The Trudeau government is behaving as a helpful fixer in Ukraine, the Koreas, Venezuela, on migration and climate issues, and at the WTO. Relations with Mexico, our third largest trading partner, improved after he lifted a pernicious visa requirement. And with the one relationship that really matters – that with the U.S. –Trudeau and his team have successfully managed Trump, fending off his tariffs, while preserving Canada’s preferred access to the U.S. market.

Security beyond our Borders

Multilateralism is integral to Canadian diplomacy. By working with like-minded nations to sustain and advance the rules-based order, we get much more leverage from our place as a middle power. Great powers can always throw their weight around. The age-old concert of great powers reduces relationships to the big dictating terms to the small. When adroitly employed, multilateralism levels the playing field. It is especially useful in time of crisis and in addressing global challenges like crime and terrorism, migration, climate change and pandemics.

After more than a decade of often frustrating experience in Afghanistan (2001-2014), Canadian troops are deployed around the world in support of collective security and peace operations. Most of our deployments are with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Canada leads a NATO brigade in Latvia, and our aircrafts, warships and submarines patrol the waters and the skies of the Atlantic and Mediterranean as part of NATO’s assurance and deterrence initiatives. There are Canadians in Iraq, again under the NATO umbrella and as a member of the Global Coalition against Daesh. Canadians wore the blue beret of UN peace operations in Mali (2018-2019) and are now in Uganda (2019-2020) with a standing commitment (2017) to supply more peacekeepers as required. Canadian air and sea forces support enforcement of the UN’s sanctions on North Korea. A half century after the armistice, we continue to contribute to the UN peace operations team in Korea’s demilitarized zone (DMZ) and now in sanctions enforcement on the high seas.

The Trudeau defence policy, Strong, Secure and Engaged (June 2017), promised strength at home, security within our continental frontiers and engagement abroad. There would be re-involvement in UN peace operations, building on previous, sometimes mythologized, experiences in Suez (1956), in Cyprus (1964-93), in the Balkans (1991-2004), in Afghanistan, and still currently in the Congo and Syria’s Golan Heights. Trudeau hosted a ministerial conference in Vancouver (2017) that resulted in The Vancouver Principles on Peacekeeping and the Prevention of the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers. But while preserving ongoing commitments, there were only two new peace operations deployments: the concluded mission in Mali and now in Uganda. While useful, it was less than what was expected, and as Jocelyn Coulon points out, more continuity than break with the Harper Conservatives.

There were commitments to rearmament, with more money and forces for the defence of Canada. The Canadian navy and coast guard will receive a new ship every year for the next 20 years. In assessing the new defence policy after two years, CGAI’s David Perry concluded that the Trudeau government is “mostly delivering”, although spending on equipment and infrastructure has lagged behind projection because of contingencies not being used, project efficiencies, industry not delivering on schedule and project delays internal to government.

Election 2019

The October 2019 election was short, nasty and vacuous. Charges of hypocrisy were laid against Trudeau for appearing in black-face and brown-face. Conservative leader Andrew Scheer was also accused of hypocrisy for holding dual Canadian-American citizenship while previously criticizing others who held dual citizenship. There were only four debates, with Trudeau participating in just three of them (two French language and one English). The foreign policy debate was cancelled.

When the election ended, Scheer’s Conservatives won the most votes: 34.4 per cent versus 33.1 per cent for the Liberals, with Jagmeet Singh’s NDP at 15.9 per cent, Yves-François Blanchet’s Bloc at 7.7 per cent and Elizabeth May’s Greens at 6.5 per cent. Yet the Liberals formed a minority government, winning 157 seats to the Tories’ 121, the Bloc’s 32, the NDP’s 24 and the Greens’ three, with Wilson-Raybould as the sole independent.

If Trudeau pulled his party to a majority in 2015, pollsters said he was a drag in 2019. But so was Scheer, and within weeks he announced he would be stepping down. May also announced it would be her last election as the Greens’ leader.

Shut out in Alberta and Saskatchewan, Trudeau said that attention to regional needs would be a top priority. He followed up with a series of individual meetings with provincial premiers. As deputy prime minister and Trudeau’s likely successor, Freeland takes on federal-provincial relations and is charged with organizing a first ministers meeting in early 2020.

Alberta Premier Jason Kenney’s request for a “fair deal” is reasonable and his argument that a strong Canada needs a strong Alberta is compelling. There will be some rebalancing in fiscal sharing arrangements, although the loser is likely to be tomorrow’s taxpayers who inevitably will have to pay the piper for deficit spending.

Foreign Policy Challenges Ahead

In Monty Hall’s long-running Let’s Make A Deal, contestants faced three doors. Behind one was a car and behind the other two were goats. For Trudeau, the goats are the continuing challenges in our relationships with the U.S. and China while the prize is winning a seat on the UN Security Council – a vindication of his commitment to internationalism.

Unfortunately for Trudeau, he has to manage all three doors.

Relations with the U.S. always come with irritants. What is remarkable is how well it works, even with Trump. Freeland stays responsible for the U.S. file. She has managed this file very well and her contacts are excellent, but splitting ministerial responsibility for the U.S. from new Foreign Affairs Minister François-Philippe Champagne will cause headaches down the road. It will complicate life for our yet-to-be-named ambassador in Washington where our embassy is effectively an adjunct to the Privy Council Office and source of advice to the Prime Minister’s Office. Effective ambassadors also have relationships with ministers and premiers.

Washington is all about power and politics and the political class – whether on Capitol Hill or in the Administration. They prefer dealing with those who understand politics, a skill not generally found in professional diplomats. Our next ambassador will require political instincts, gravitas and knowledge of the U.S. Former ministers or premiers who have these qualities include Rona Ambrose, Jean Charest, Peter Mackay, John Manley, Anne McLellan, Bob Rae and Brad Wall (although some of these may soon be seeking the Conservative leadership). To succeed, our new ambassador also needs the confidence of the prime minister. Otherwise the White House will go direct to the prime minister’s office. The ambassador should also work closely with the U.S. ambassador in Ottawa – as quarterbacks in the field, the two ambassadors can resolve a lot of the transactional problems.

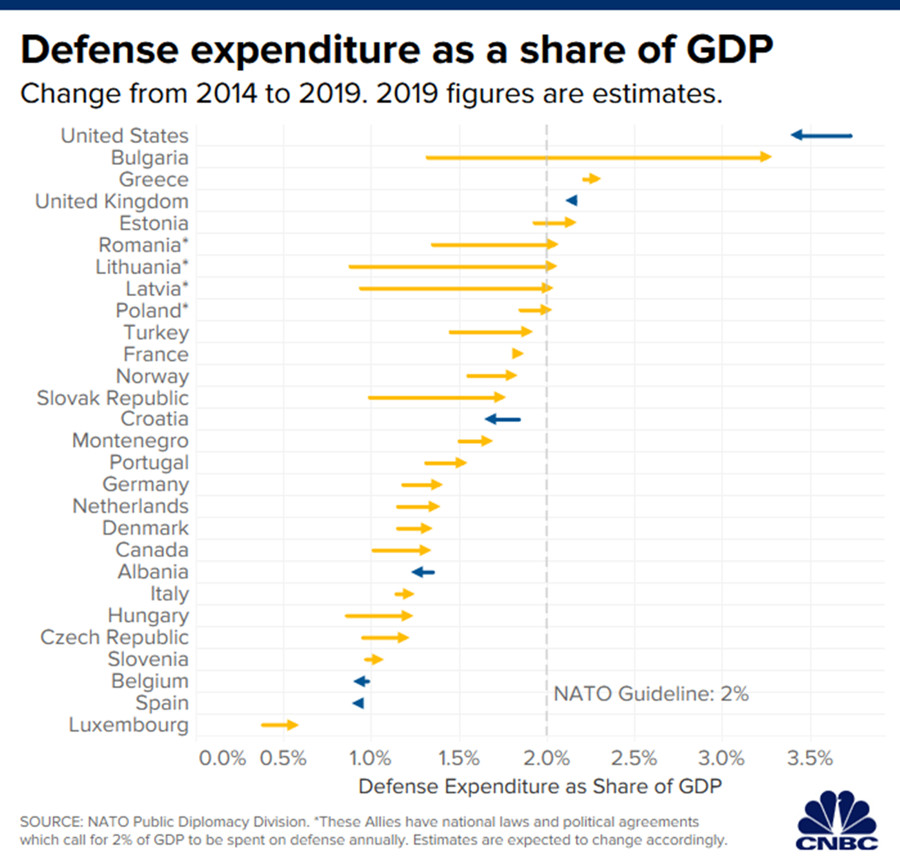

The Trump administration expects more from Canada on defence and security. For Trump, the metric is spending two per cent of GDP. An increased NATO commitment is the first instalment. Lost in the foofaraw around an off-mic comment dissing Trump at the London summit (December 2019), is the fact that Trudeau committed more naval and air support to the 70-year-old security alliance.

What the Americans really want is for Canada to exercise the sovereignty it claims in the Arctic. In practical terms, this means upgrading the North Warning System.

Fixing the Safe Third Country Agreement with the U.S., promised in the throne speech, is another challenge. Porous borders feed populism and help breed legislation like Quebec’s Bill 21. Requiring potential refugees to apply for sanctuary in the country where they first land – the Safe Third Country Agreement – was one of the accomplishments of the Chrétien government when then-Foreign Affairs minister John Manley negotiated the “smart border” accord with Homeland Security’s Tom Ridge. The Trump administration should go along; the U.S. wants a similar agreement from Mexico.

Managing the trading relationships, especially trade diversification, is another permanent challenge; Pierre Trudeau pursued ‘counterweights’ and the ‘Third Option’ to reduce trade dependence on the USA. Freeland’s first assignment was negotiating the new NAFTA. The prerequisite for the Trump administration was to achieve legislative passage through the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives. The major changes – tougher enforcement on environment and labour – were aimed at and swallowed by Mexico, although they did wrest a dispute settlement panel provision that will serve Canadian interests. The other changes – patent protection for biologic drugs consistent with the CPTPP and steel made in North America – did not disadvantage Canada. Having passed the House, it should sail through the Senate after the impeachment proceedings. It should also get through the Canadian Parliament.

While experts question the gains in the new NAFTA with its increasingly managed trade, it does provide the required stability that foreign and Canadian investors expect. Canada’s exports are the fourth most concentrated by destination out of 113 countries. Can we convince Canadian business to use the new transoceanic trade relationships? How much collateral damage will the ongoing Sino-U.S. trade war inflict, and if it is resolved, will we find ourselves at a disadvantage vis-a-vis our American competition, especially when it comes to our agri-food industry?

The second major test is China and the requirement for realism in dealing with a rising superpower that is increasingly aggressive abroad and repressive at home.

The government’s handling of the Meng affair and its fallout is tactically suspect. Elevating the extradition to the sanctity of “rule of law” has confused the Chinese and left us with little room to maneuver. Trudeau’s request of Trump not to sign any agreement with China until the hostages are freed would seem to misunderstand Trump and his art of the deal, while for the Chinese we simply look weak. It plays to their evaluation of Canada as a vassal state of the U.S. – a running dog of U.S. imperialism. Jean Chrétien, who understands China, is likely right when he characterizes our China debacle as “a trap that was set to us by Trump, and then it was very unfair, because we paid the price for something that Trump wanted us to do.”

If the Trudeau government needed reminding that it no longer enjoys a majority, the Conservatives introduced – on the one-year anniversary of China’s detention of hostages Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig – a motion creating an all-party parliamentary committee to assess and monitor Canada’s relations with China. Despite Liberal opposition, the resolution passed with the support of the NDP and Bloc Québécois. If they can park partisanship at the door, the all-party committee might just achieve a realistic China policy that all can support. For too long, our China policy has teetered between the romantic and the hostile, depending on whether the government is Liberal or Conservative. Its only common thread was a cloak of government secrecy. Inconsistent and opaque policy serves neither our interests nor our values.

The third major test will come in June 2020 when Canada competes with Ireland and Norway for a two-year seat on the United Nations Security Council. The fatalists may be right about us losing, but a second loss will be traumatic for the government and a shock to Canadians. Losing in 2010 could be rationalized as the Harper government having run a lackluster campaign due to ambivalence about the UN and taking perverse pride in the mantra “we don’t just go along to get along.”

To win will require more active campaigning by ministers and Trudeau in Eastern Europe, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and drawing on our ties within the Commonwealth and la Francophonie. We have a good ambassador in Marc-André Blanchard and a credible platform built around combating climate change, promoting gender equality, promoting peace and economic security, and a commitment to multilateralism.

And if we win, then we will have to deliver on our promises. This will mean more resources – people and money – for our UN missions. The Trudeau government has gotten away with little investment in our foreign affairs. If we want to be effective it also means we will need to open embassies in places like Pyongyang and Teheran. If their governments are corrupt or abusing human rights, we should use our Magnitsky sanctions on individuals rather than shutting down our embassies. Diplomatic relations are not a seal of approval but rather the means by which we conduct business, most of it having to do with people-to-people transactions – visas for students, migrants and business as well as the classic consular work of helping Canadians in distress – in addition to the high politics. If we want to provide a Canadian perspective to a situation, it starts with being there – having trained diplomats who look, listen and when necessary speak out to advance Canadian interests.

“Canada is back” is a conceit. The Trudeau record does not match the rhetoric: Canada still falls short (1.31 per cent of GDP) of the NATO target of two per cent of GDP on defence spending. Our international development assistance (0.264 per cent of GDP) remains well short of the 0.7 per cent endorsed by the G7. Mulroney got it right when he described our spending as a “disgrace” and asked: “How are you going to assert your leadership skills when you enter a room and somebody says, ‘Hey, you haven’t paid your bills’.”

If we want to make a difference – to achieve a progressive agenda, to diversify trade, to be a credible security partner – then the Trudeau government is going to have to invest more in defence, in development and in its foreign service.

Concluding Observations

Born on Christmas Day 1971, this charismatic son of the equally charismatic Pierre Trudeau initially held Canadians and the world in thrall. A natural cheerleader who likes to be liked, Justin Trudeau is at his best when the going is good. When the going gets tough, Trudeau is sometimes indecisive, at a loss about what to do next. Unfortunately for Trudeau and for Canada, these are treacherous times. We live in an age of populism and protectionism. Democracy is on the downslide. The rules-based order with its internationalist norms are broken with impunity. This breakdown only seems to encourage more bad behaviour. Democratically-elected leaders are now as likely to look like Trump as Trudeau. Mr. Trudeau is learning firsthand what British prime minister Harold MacMillan warned U.S. president John F. Kennedy what was most likely to blow governments off-course: “Events, dear boy, events.”

Identity politics is central to the Trudeau team’s playbook. But what politicos say plays domestically can back-fire internationally. The problem with the shambolic magical mystery tour to India was not in the costume changes but the setback to relations with India when it appeared that we put domestic politics ahead of what India saw as their legitimate security concerns.

All governments focus on style and stagecraft, but the Trudeau team takes it to a new level through use of social media. But selfies, tweets and celebrity status are volatile. The once APEC “hottie” is caricatured for dress-up involving black- and brown-face, episodes that occurred long before he entered politics. Trudeau is no racist, but the incidents and his initial response when challenged on them raised questions about his judgment for which he paid a price in the 2019 election.

Some prime ministers are transformational. Fewer are consequential. Pierre Trudeau was both. Whether Justin Trudeau will match his father is still to be determined but no one is forecasting sunny ways anymore.

Leadership depends on winning respect through achievements and Justin Trudeau has led on issues of climate, diversity, and migration. He has well managed our most important relationship, that with the USA, despite the challenges of Donald Trump. Building on Mr. Harper’s initiatives, he has opened the way for trade diversification across the Pacific and Atlantic, while preserving freer trade within North American. He has made necessary and overdue investments in defence, but procurement must be fixed. We need to invest more in development and in diplomacy. Then we might be able to claim that ‘Canada is back’.

About the Author

A former Canadian diplomat, Colin Robertson is Vice President and Fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute and hosts its regular Global Exchange podcast. He is an Executive Fellow at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy and a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs at Carleton University. Robertson sits on the advisory councils of the Johnson-Shoyama School of Public Policy, North American Research Partnership, The Winston Churchill Society of Ottawa and the Conference of Defence Associations Institute and the North American Forum. He is an Honorary Captain (Royal Canadian Navy) assigned to the Strategic Communications Directorate. During his foreign service career, he served as first Head of the Advocacy Secretariat and Minister at the Canadian Embassy in Washington and Consul General in Los Angeles, as Consul and Counsellor in Hong Kong and in New York at the UN and Consulate General. A member of the teams that negotiated the Canada-U.S. FTA and then the NAFTA, he is a member of the Deputy Minister of International Trade’s Trade Advisory Council and the Department of National Defence’s Defence Advisory Board. He writes on foreign affairs for the Globe and Mail and he is a frequent contributor to other media. The Hill Times has named named him as one of those that influence Canadian foreign policy.