Ottawa needs to rethink its business subsidies

The federal government announced on April 20 how much it will cost Canadian taxpayers to get Volkswagen to build an electric vehicle battery manufacturing plant in Ontario. Ottawa will subsidize about 10 percent of the $700 million capital cost of the facility and will provide up to $130 million a year in production subsidies over ten years starting in 2027, when the plant is expected to start producing batteries.

The federal government has emphasized the need to level the playing field with the US after the implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Indeed, the Volkswagen production subsidy matches what is available in the US. However, my analysis of the data indicates that US business subsidies for clean fuels and clean technology under the IRA are less generous than their Canadian counterparts.

Based CBO costing, US non-agricultural business subsidies in the IRA will amount to about $60 billion from 2022 to 2026 and $160 billion from 2027 to 2031. That’s .04% and .09% of US GDP, respectively. In Canada, funding for the Net Zero Accelerator is $8 billion over 7 years and funding for the rest of the Strategic Innovation Fund is $18 billion over 13 years. Over the 2022-26 period, that works out to about .09% of GDP. And that is just the cost of two programs. The five refundable tax credits announced since 2021 that support clean fuels, clean technology, and carbon capture, storage and use, will add about .13 percent of GDP to the cost of subsidies over the 2023-25 period. Other subsidies targeting clean fuels and clean technologies will amount to almost .1% of GDP over the same period.

Canada is clearly not lagging the US in the clean economy subsidy “race”. But about 60 percent of US support comes from production subsidies, which, based on the Volkswagen example, appear to be more effective in attracting footloose firms than the investment subsidies favoured by Canada.

If Canada decides to make more use of production subsidies, they should be funded by repurposing existing business subsidy programs. The prime candidates for this reallocation are two industrial policy measures promoting low carbon production, the Clean Technology Manufacturing investment tax credit and the Strategic Innovation Fund (excluding the Net Zero Accelerator). Spending under these two programs is expected to be $2.2 billion in 2024-25 and about $2.7 billion in 2027-28.

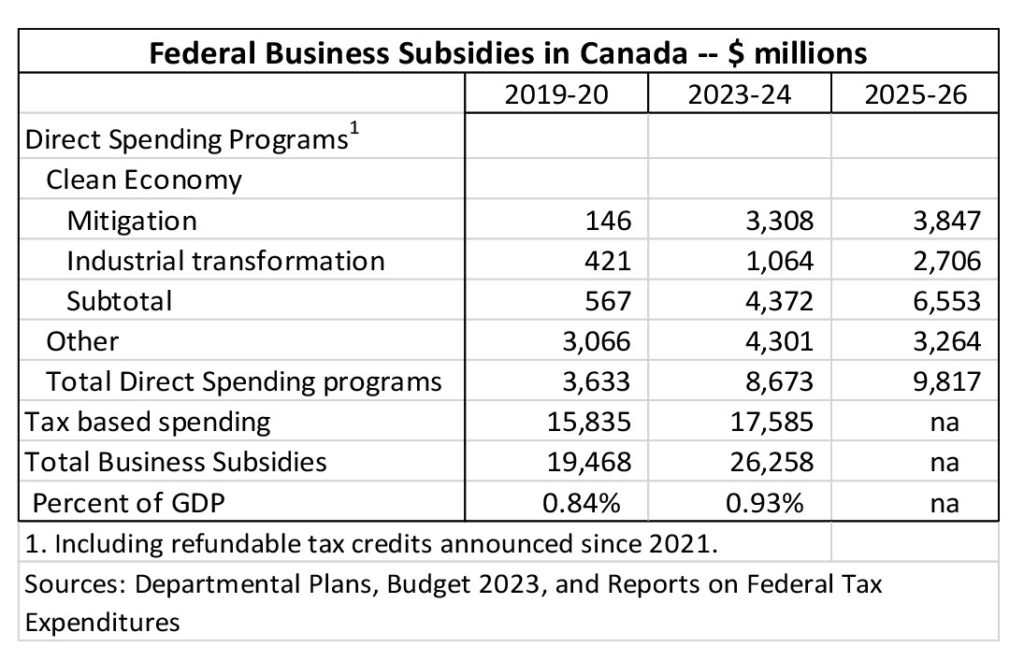

A more general point is that a broader assessment of business subsidies is needed. Spending on subsidies in the current fiscal year will be $8.7 billion, up almost 140 percent since 2019-20, and is projected to rise to $9.8 billion by 2025-26 (Table).

Almost all of the increase from 2019-20 to 2025-26 is due to new clean economy measures, but “legacy” subsidies will amount to $3.3 billion in 2025-26, up about 6% from their level in 2019-20. The federal government has argued that subsidies are necessary for Canada to obtain its fair share of investment in the emerging clean economy, but does it make sense to support the existing industrial structure at the same time? Shouldn’t some of the funding for the new initiatives come from legacy programs in order to facilitate the shift in labour and capital to the clean economy?

The need for a review becomes more acute when it is recognized that direct spending programs account for only a third of business subsidies provided by Ottawa. Business subsidies delivered through the tax system, excluding the clean economy refundable tax credits and most measures providing accelerated capital cost allowances, are expected to cost $17.6 billion in 2023, bringing total support to $26.3 billion. That represents .9 percent of GDP, up from .8 percent in 2019-20 and about .7 percent in 2014-15, the last year of the Harper government.

A prudent fiscal manager would have reviewed existing measures and adjusted or eliminated the weakest performers to fund the industrial transformation to a clean economy. Ideally, the government would adopt a funding envelope for business subsidies, expressed as a share of GDP, in order to ensure spending reflects current priorities and represents the best value for money. Returning business subsidies to their 2019-20 share of GDP would require a $3 billion reduction, while planned spending would have to be trimmed about $8 billion to reach their 2014-15 share of GDP.