Hybrid Cars (Part One): How Many Roads Must a Hybrid Drive Down?

Originally, hybrid cars were marketed primarily to environmentally-conscious consumers. Manufacturers and their marketing departments expected these consumers, who have a stated preference for reduced hydrocarbon emissions and increased environmental protection, to pay a premium for increased fuel economy and lower emissions.

Increasingly, hybrid cars are being marketed to a wider consumer base citing increased fuel economy as a cost-saving measure. An increase in fuel economy reduces the gas consumed per mile and therefore reduces the variable cost associated with driving. But is paying more for a hybrid model actually an effective strategy for saving costs? This blog post takes a quick look at some of the numbers to see if investing in a hybrid will really pay off.

To appropriately evaluate the potential cost savings from buying a hybrid, we need to compare two very similar vehicles. The Honda Accord comes in both a standard gasoline and plug-in hybrid model. A standard gasoline Accord (LX model with V6 engine and manual transmission) carries a manufacturer’s suggested retail price of $23,990 (Canadian). The plug-in hybrid model has an MSRP of $29,590. Given that the equipment on these two models is basically identical, the increased fuel economy of the hybrid will cost a consumer $5,600.[1] So when we talk about “investing in a hybrid,” this $5,600 is the “fixed cost” or investment, while the return on investment will occur over time as reductions in the “variable cost” of gasoline purchases.[2]

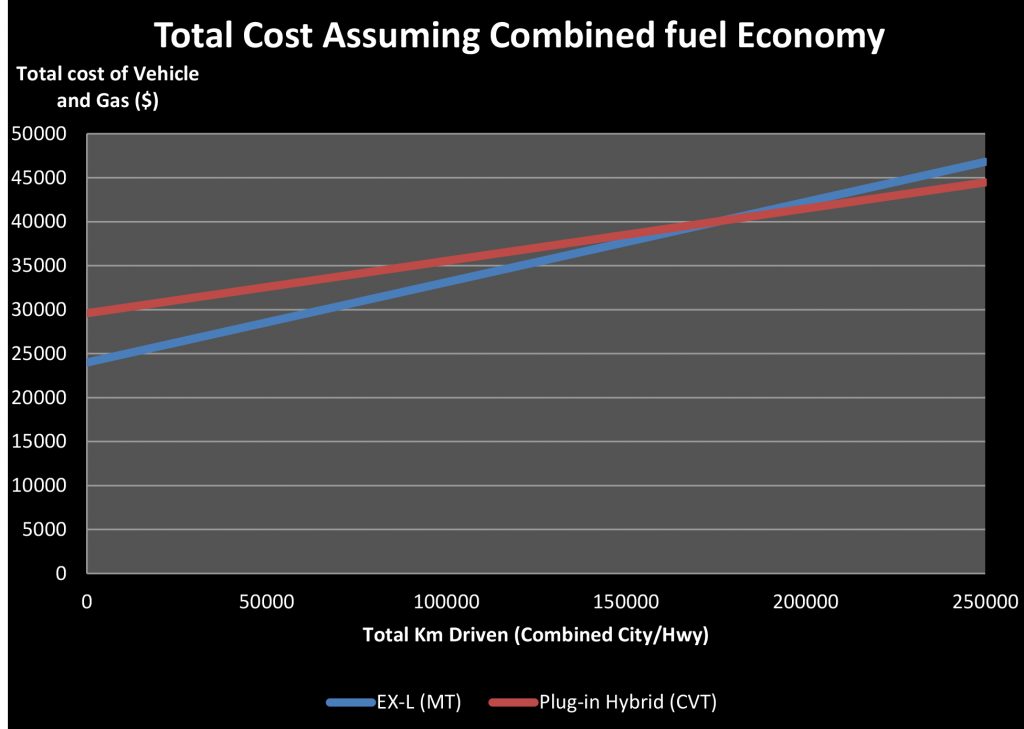

The gasoline version has a combined city/highway mileage of 7.84 L/100km (30MPG)[3] while the hybrid has a combined city/highway mileage of 5.11 L/100km (46MPG).[4] So, for every 100 km driven, the hybrid saves about 2.73 litres of gasoline for an average driver. Last week, the average price for regular unleaded in Alberta was $1.16/L,[5] which means that for every 100 km, the hybrid would save its driver about $3.17. At that rate, it will take more than 177,000km of driving before the variable cost savings of owning a hybrid offsets the additional purchase price. Figure 1 shows the total cost of operation (excluding maintenance) for both models over time.

Figure 1: Total Cost of Operation Assuming Combined City/Highway Fuel Economy (Nominal Dollars)

The above graph paints a bleak picture for the cost saving prospects of owning a hybrid. Data from Statistics Canada indicates the average Canadian drives about 16,249km per year.[6] This means that it would take 11 years to save enough on gas to pay for the additional cost of a hybrid and depending on driving style, it could take even longer.

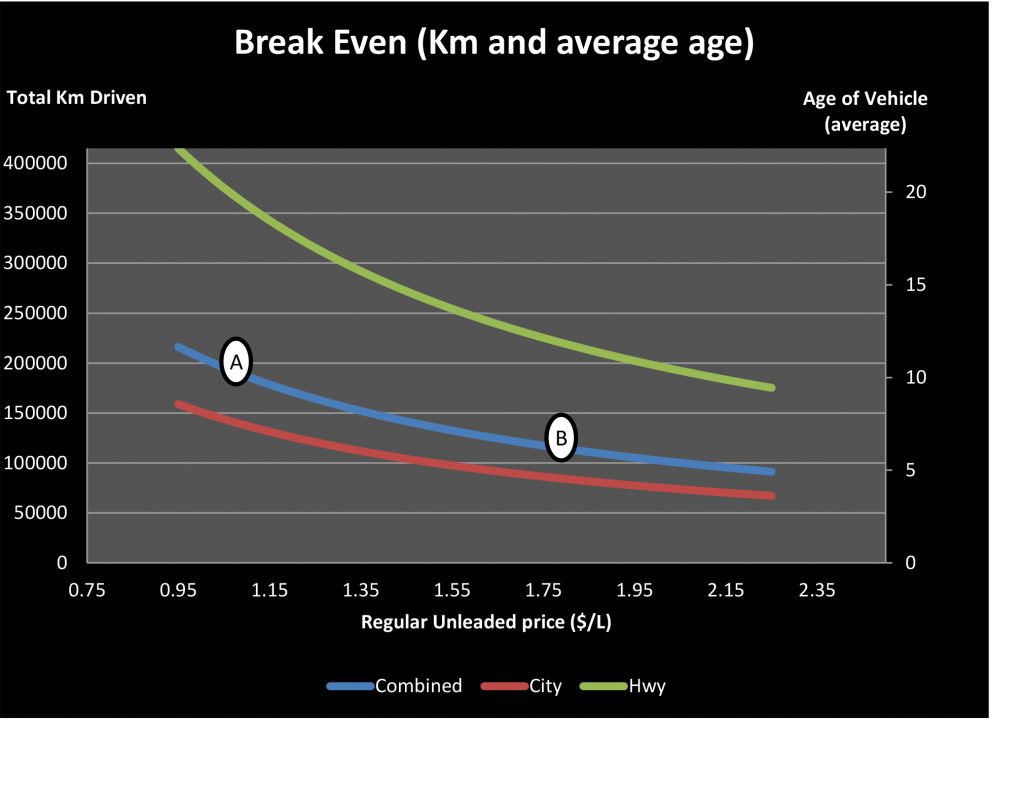

Hybrid cars get much better city mileage (low speeds, lots of stopping and starting) than conventional engines, but do not perform that much better at highway speeds. Figure 2 below gives the break-even mileage/age of a hybrid for three different driving styles over a range of prospective retail gasoline prices.

Figure 2: Break-Even Point as a Function of Gas Prices

Figure 2 indicates the total kilometers (and vehicle age, given the average km/year for a Canadian driver) it will take a hybrid owner to break even (realize enough savings on gasoline purchases to offset the additional cost of buying a hybrid). As the price of gas increases, the total savings for a given distance traveled increase and the break-even point shrinks. Figure 2 gives this relationship for three different driving styles; highway driving only (green), city driving only (red) and combined city-highway driving (blue).

It’s no surprise that, the higher the price of gas, the less time it takes to recoup the investment. A $0.70/L increase in the price of gasoline moves the break-even point from 11 years (point A) to around 6 (point B) for a driver mixing between city and highway driving. However, for a driver that drives primarily on the highway, even at a gas price over $2.00/L, it will still take 10 years to break even.

Looking at the break-even point for a hybrid’s total cost indicates a gloomy prognosis for the prospect of the “cost-saving hybrid.” Purchasing a Hybrid in order to save some cash is likely not an effective strategy unless the consumer plans to keep the car for a long time and/or does a relatively high amount of city driving every year.

The second half of this blog post will look at “return on investment” as a metric for evaluating hybrid cars. Treating the additional expense of owning a hybrid as an investment (and factoring in the resale price of the car) can indicate a different prognosis for the financial implications of owning a hybrid under certain conditions.

[2] For this exercise, additional costs like insurance and maintenance are ignored.

[6] 2009 data: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/53-223-x/2009000/aftertoc-aprestdm1-eng.htm Associated CANSIM tables are 405-0055 through 405-0120. The vehicle survey was discontinued after 2009.