Political Science and City Elections: Local Campaign Finance

Calgary is a big, diverse, vibrant city. We’re proud of our western heritage, but we’re also keen for outsiders to recognize that Calgary is more than just cowboys and pickle corn dogs. Still, in one important respect, people across the country regularly call Calgary the “wild west” – campaign finance. As we’ll see, they’re probably right to do so.

To understand how campaign finance works in Calgary, it helps to divide the rules into two categories: rules about fundraising (how you get your money) and rules about expenditures (how you spend your money). On the fundraising side, the most important rules are about who is allowed to donate and how much they’re allowed to give. On the expenditure side, the rules are about who can spend money during elections and how much they’re allowed to spend. Put these rules together and you have a pretty good picture of a city’s campaign finance system.

In Calgary, the rules in both of these categories range from lax to nonexistent. On the fundraising side of the equation, candidates can get their money from any person or organization in Alberta. This includes non-profit agencies, unions, and corporations – as long as they have active operations in Alberta, they’re allowed to donate to municipal candidates. Each person or organization can give up to $5,000 per year to any candidate. With four years between elections, this means that a candidate can potentially receive up to $20,000 from each donor. Candidates are required to disclose any donations above $100, but there may be ways to get around this disclosure rule by channeling money through third-party organizations – a loophole that is an ongoing source of controversy in Calgary.

On the spending side, the sky is the limit: you can spend as much as you want. This creates something of a fundraising “arms race”, especially in competitive elections. In 2013, for example, the contentious three-way race in Ward 7 between Druh Farrell, Kevin Taylor, and Brent Alexander resulted in a whopping $461,000 in total campaign expenditures. Across the 2013 election as a whole, candidates spent an average of $81,000 on their campaigns, amounting to about $11 for each vote that a candidate received. Plus, if you don’t spend all of the money that you raise, you’re allowed to keep it as a “war chest” for the next election.

How high are these numbers in comparative terms? It’s useful to compare Calgary to Toronto, which is widely seen as having an up-to-date and quite strict set of campaign finance rules. In Toronto, each individual is allowed to give no more than $750 to a council candidate, and no more than $5,000 in total across the election as a whole. Donations from advocacy groups, corporations, and unions are totally banned. War chests are prohibited. Campaign spending limits are capped at $5,000 plus eighty-five cents per elector, which works out to between $25,000 and $50,000 dollars depending on the size of the ward. All of this adds up much cheaper elections: even though the 2014 Toronto election had eight times more candidates than Calgary in 2013, spread across 44 wards instead of 14, the total amount spent in Toronto was less than double the Calgary numbers: $5.26 million in Toronto, and $3.4 million in Calgary.

Does any of this actually matter? Do different campaign finance rules actually affect who wins and who loses? The political science research on this question is quite mixed. One very detailed study from the United States concluded that donation rules and spending limits have not made American local elections more competitive. Spending limits might actually make it more difficult for challengers to reach voters, reinforcing the advantage of incumbents, and limits on individual donations might do little more than drive money to third parties.

In Canada, a recent study of the 2014 Toronto election found that incumbents spent almost three times more than their opponents per elector. Toronto’s strict spending caps seemed to have no effect, as very few candidates, whether incumbents or challengers, came even close to reaching them. On average, winning candidates spent 82% of their limit, against 46% for serious candidates (those who raised more than $1000) who were not elected.

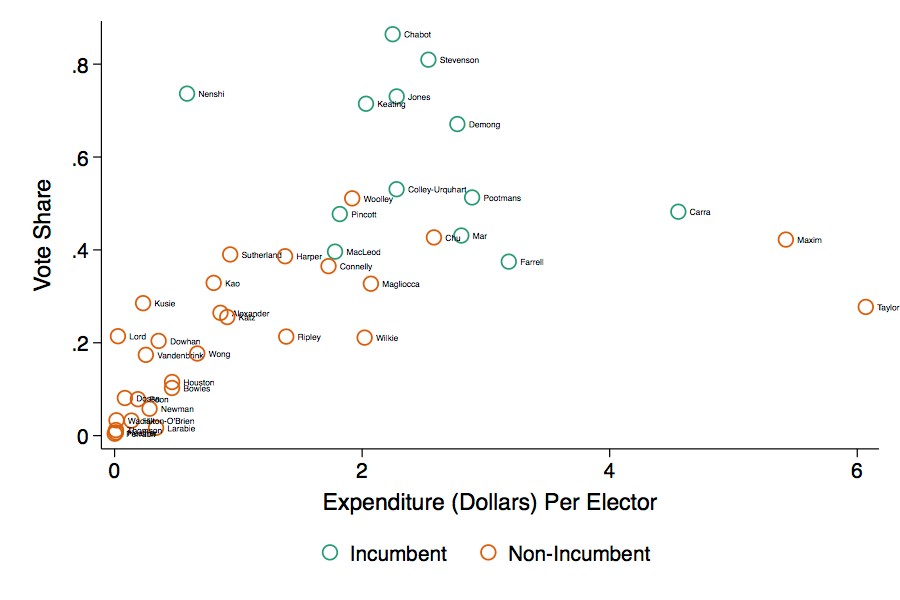

So do incumbents win because they raise the most money, or do they raise the most money because they are highly visible candidates who are likely to win? In Toronto, the answer actually seems to be the latter — and from a political science perspective, this is a bit strange. Studies of the U.S. Congress, for example, find that the more secure incumbents are, the less money they spend; if you see a member of Congress spending big money, you can assume that they’re feeling vulnerable. But in Toronto, it seems that incumbents are able to hoover up campaign donations with little effort, even if their spending turns out to have little effect on campaign outcomes. The figure below suggests that the same dynamic was probably true in Calgary in 2013. Incumbent candidates (in green) raised more money than challengers (in orange) while also winning much higher vote shares in their wards

What would it take to level the playing field in Calgary’s municipal elections? Low spending caps and strict donation limits would probably help incumbents as much as challengers, and might even make the incumbent advantage stronger. Some in the United States have argued that we need to make it easier for candidates to enter municipal races, and increase voters’ knowledge about incumbents. In Canada, by contrast, part of the problem might be that running for election is actually too easy – in Toronto, 40% of candidates in 2014 raised and spent almost no money at all, suggesting that they had no intention of seriously campaigning. In an election with seven or eight candidates, it is easy for the incumbent to drown out the under resourced challengers. The best way to help serious challengers compete is by increasing voters’ knowledge of the candidates, perhaps by distributing a voter’s guide to each household summarizing each candidate’s background and commitments – or, as Calgary has done, by recording and hosting videos and other information about each candidate on an official website.

There may be good reasons to support campaign finance reform even if fundraising and spending limits don’t have any clear effect on election results. Clearer disclosure rules for third-party advertising would make third-party campaigns like “Save Calgary” more transparent and less controversial. Reduced donation limits would mean more grassroots fundraising. A strict overall spending limit would make elections cheaper for everyone. Few would object to these principles – which is why the Alberta Government is likely to introduce new municipal campaign finance rules for Calgary and other Alberta cities next year. This might be Calgary’s final election under our “wild west” campaign finance rules. But don’t worry – we’ll always have pickle corn dogs.

Click here to sign up for the Calgary Municipal Election Newsletter. For other briefings, on topics such as incumbency, political parties, and women in city politics, click here.