Rebalancing Calgary’s Property Taxes

Introduction

The City of Calgary’s property tax conundrum has been well documented in the local print media. (See Potikin 2018 and Varcoe 2018a,b,c.) The high vacancy rates in the downtown office buildings has resulted in a sharp decline in the assessed value of these properties. Under the City of Calgary’s so-called revenue neutral property tax rate setting policy, the decline in the assessed values of these office building has resulted in an sharp increase in the non-residential property tax rate in order to continue raising a large share of property tax revenues from non-residential properties. The result has been a sharp increase in the property taxes levied on commercial and industrial properties outside Calgary’s core. To shield these properties from tax increases in excess of 5 per cent, the City transferred $45 million from its Community Economic Resiliency in 2017 and $41 million from its Fiscal Stability Reserve in 2018. The recent Chief Financial Officer’s Report to the Priorities and Finance Committee indicates that, based on preliminary assessment data for 2019, there has been a further $4 billion dollar decline in the value of the downtown offices. Under its current policies of maintaining the level of non-residential property tax revenues, the City will have to increase its non-residential mill rate in order to offset the decline in the assessed value of the office towers. This tax rate hike is forecast to increase the property tax payment of a commercial or industrial property, that has not changed in value, by 17 per cent in 2019. The report estimates that if the City is to again limit non-residential property tax increases to 5 per cent, it will have to further dip into its reserve funds to the tune of $89 million. Having spent $175 million over three years to limit tax increases and with no revival in the office real estate market in sight, the City’s current tax policies are clearly unsustainable.

What is to be done? This blog provides background to City’s property tax rate setting policies. We argue that while other fiscal measures should be investigated, rebalancing property taxes collected from the non-residential to residential properties should be part of the solution. This is not a popular policy, but if Calgarians want to maintain a vibrant business climate that generates employment opportunities, especially in the industrial and commercial sectors, more of the burden of financing the City’s services will have to be borne by homeowners.

Background

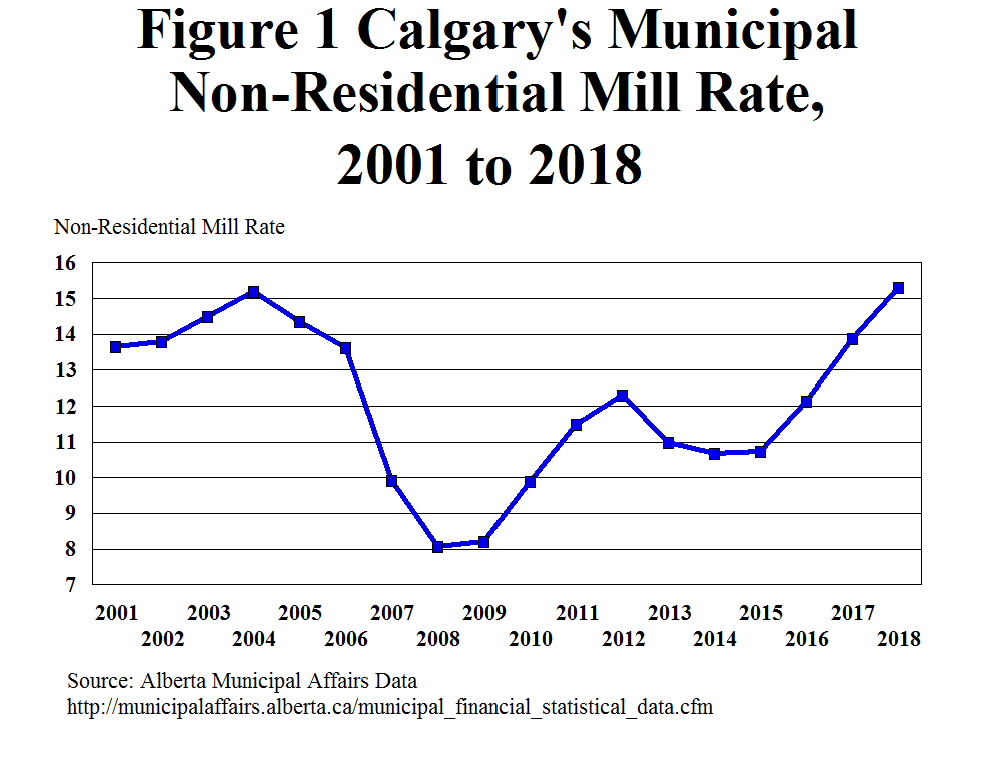

The recent and projected increases in the municipal non-residential property tax rate is at the heart of the fiscal issues confronting Calgary. Figure 1 helps to put these recent increases in perspective by plotting the municipal non-residential mill rate since 2001. (The mill rate is the tax rate per $1000 of property value.) The municipal non-residential mill rate has almost doubled over the last 10 years, but in the early 2000s the rate was almost as high as it is now. Clearly, there have been large and rapid swings in the municipal non-residential mill rate over the last two decades. Given that property taxes are the largest taxes imposed on many small and medium sized businesses, the fluctuations in the property taxes poses special challenges for the business sector.

The increase in the tax burden on the non-residential sector has been partly offset by the gradual elimination of the business tax, which has declined from $206.7 million in 2013 to $44.6 million in 2018. As a result, businesses’ share of total property tax and business tax revenues has remained relatively constant at 57 per cent in 2018.

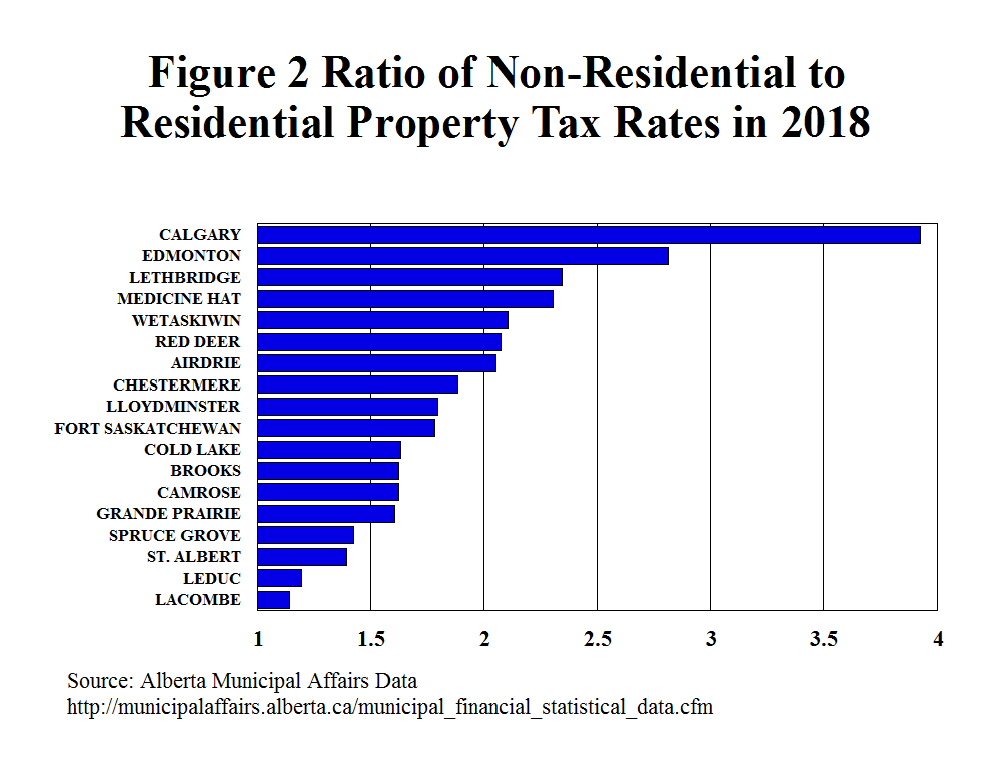

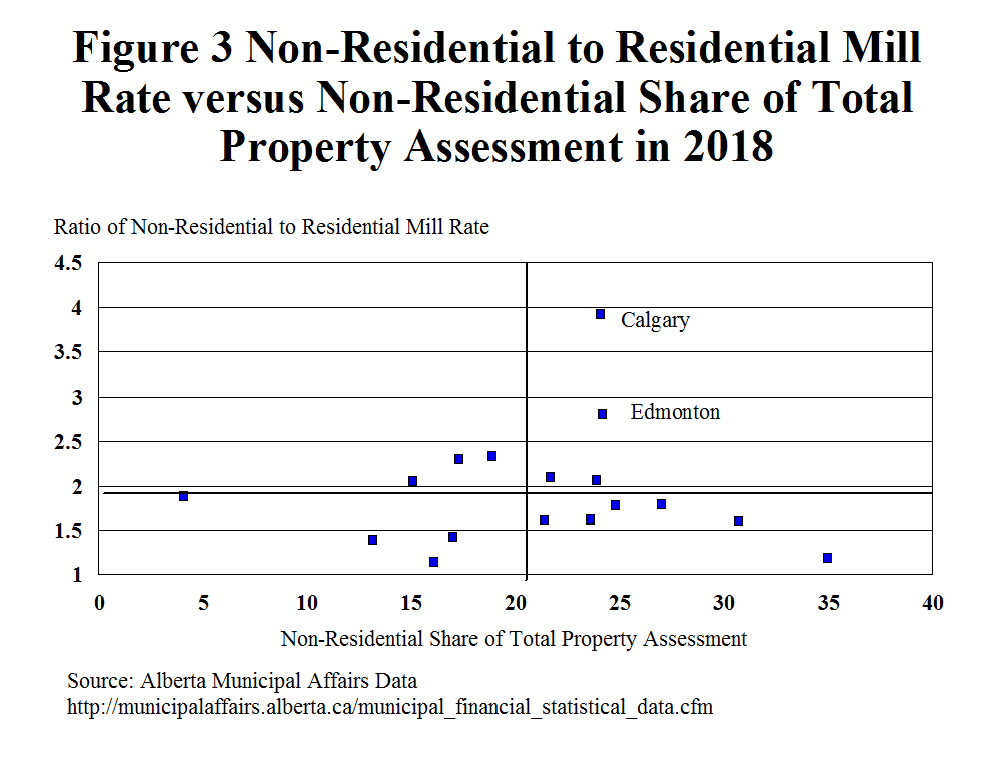

The City of Calgary, like other municipalities in Alberta, imposes a higher tax rate on non-residential property than on residential property. In 2018, Calgary’s non-residential mill rate is 15.3234 mills, almost four times higher than the municipal residential mill rate of 3.9014. Calgary has the highest ratio of non-residential to residential mill rates among the Alberta cities as shown in Figure 2. The Municipal Government Act limits the ratio of the non-residential to residential mill rate to five to one. However, even the provincial government’s Education Property Tax imposes a higher tax rate on non-residential property than on residential property.[1] The arguments that are made for taxing non-residential property at a higher rate than residential property will be discussed in the next section.

[1] Since 2001, the provincial non-residential education property tax rate has average 1.5 times the residential property tax rate.

Calgary is particularly dependent on non-residential property tax revenues because it imposes the highest rate on non-residential property relative to the residential rate and because non-residential property is a relatively large share of its total property tax base. As shown in Figure 3, Calgary and Edmonton have both have ratios of non-residential to residential property tax rate and relatively high shares on non-residential property in the total property tax assessments. The other cities with these characteristics are Red Deer and Wetaskiwin.

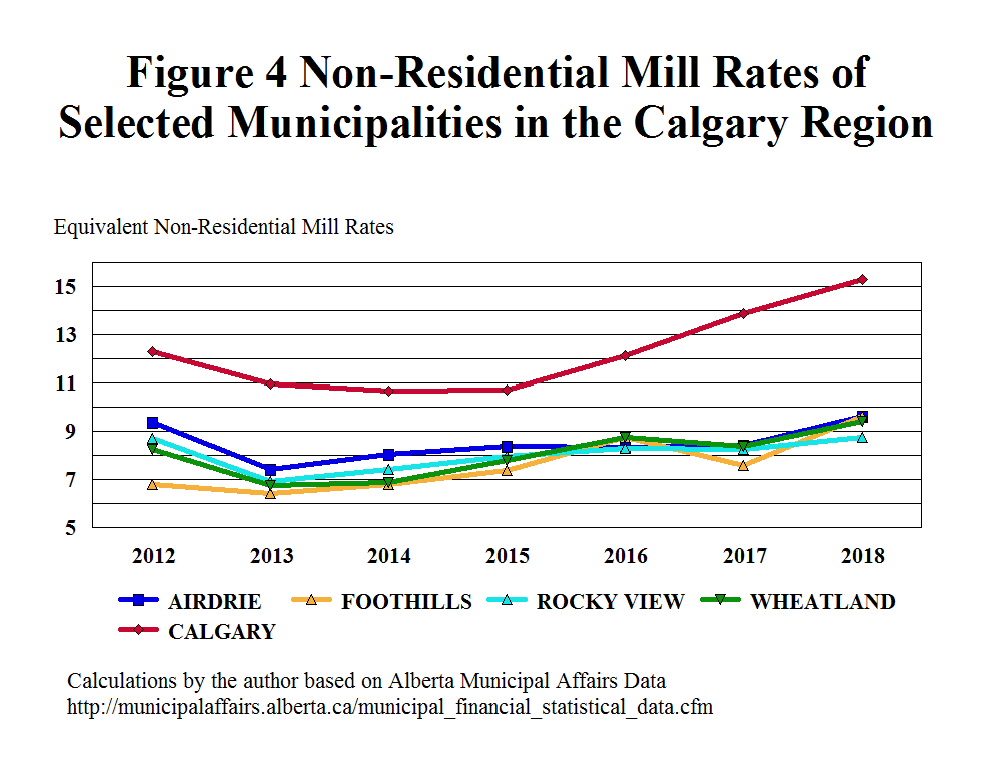

Calgary’s high non-residential property tax rate may affect its ability to attract new commercial and industrial investment, especially as its rate is now much higher than in the surrounding municipalities of Rocky View, Foothills, Wheatland, and Airdrie. Figure 4 shows that the Calgary’s non-residential mill rate is now almost six mills higher than in the four surrounding municipalities. On a $100 million investment in a new shopping centre or industrial development, this is an extra $600,000 per year in property tax, perhaps enough to shift future commercial and industrial developments beyond Calgary’s borders.

As noted above, the recent report of the City’s Chief Financial Officer forecasts a further decline in the value of the downtown offices and based on the City’s existing tax policy, this could see a 22 per cent increase in the municipal non-residential mill rate from 15.3234 in 2018 to 18.634 mills in 2019. [2] Assuming that the residential property tax remains unchanged, this means that the ratio of the non-residential to residential mill rate in Calgary in 2019 will be 4.78, which is getting close to the maximum ratio allowed under the Municipal Government Act. Clearly if current trends continue, the City could hit the maximum allowed ratio. Before that happens, thorough review of the current property tax polices and other fiscal instruments should be undertaken. Below we provide some thoughts on rebalancing the property tax burden in Calgary between residential and non-residential properties.

[2] My calculation of the 2019 mill rate is based on the projected tax rate increase for a $500,000 assessment in the Chief Financial Officers report and the assumption that the Education Property tax rate remains the same as in 2018.

Policy Issues

Calgary’s tax rates on non-residential property are escalating because of its policy of maintaining a large share of total property tax revenues from non-residential property whether or not total non-residential assessments are increasing or decreasing. As we have seen, the non-residential business sector contributes over half of the total property and business tax revenues. Is there any rationale for collecting such a large share of the City’s revenues from the business sector?

One justification would be that the businesses in Calgary receive a larger share of the benefits of municipal services than residents. While it is very difficult to measure and compare the public services received by businesses and residents, it seems unlikely that the cost of providing municipal services to businesses is 3.9 times as large.

Mintz and Roberts (2006) and others have argued that over taxation of businesses and under taxation of homeowners by municipal governments is a problem across Canada. What accounts for this over reliance on business taxation by municipal governments? The simplest explanation is that municipal politicians think that taxes on business are largely borne by non-residents who do not vote in local elections. Since the tax on residential property is one of the most visible and unpopular of taxes, municipal politicians are simply responding to the political pressures of “Don’t tax me, don’t tax me, tax the other guy behind the tree.” But the long-term consequences of local governments’ excessive taxation of business is to reduce business competitiveness local, provincially and nationally. In a series of reports from the C.D. Howe Institute, Found and Tomlinson (2017) has shown that municipal business taxes drive up the marginal effective tax rate (METR) on investment. Econometric studies, survey by Dahlby and Hassett (2018), indicate that private sector investment declines with higher marginal effective tax rates. While the studies by Found indicate that the METR on investment in Calgary is comparable to the METR in Toronto, municipal taxes account for over 40 per cent of the overall METR on investment in Calgary compared to 25 per cent in Toronto. From an Alberta-wide perspective, the Calgary’s business taxes are a major competitiveness issue.

What is to be done?

There is a strong case for reducing the City’s reliance on non-residential property tax revenues in financing municipal services. While a number of fiscal measures should be considered, including increasing user fees for services that are now solely or partially funded from tax revenues, a rebalancing of the property tax between the residential and non-residential ratepayers needs to be considered, as unpopular as this might be. Any abrupt change, such as moving quickly to the 1.5 to one ratio that is applied by the provincial government under the Education Property Tax would see the tax burden on a typical single family home increase by 50 per cent. Such an abrupt adjustment would impose a severe hardship on many Calgary families whose budgets have been stretched by the downturn in the local economy.

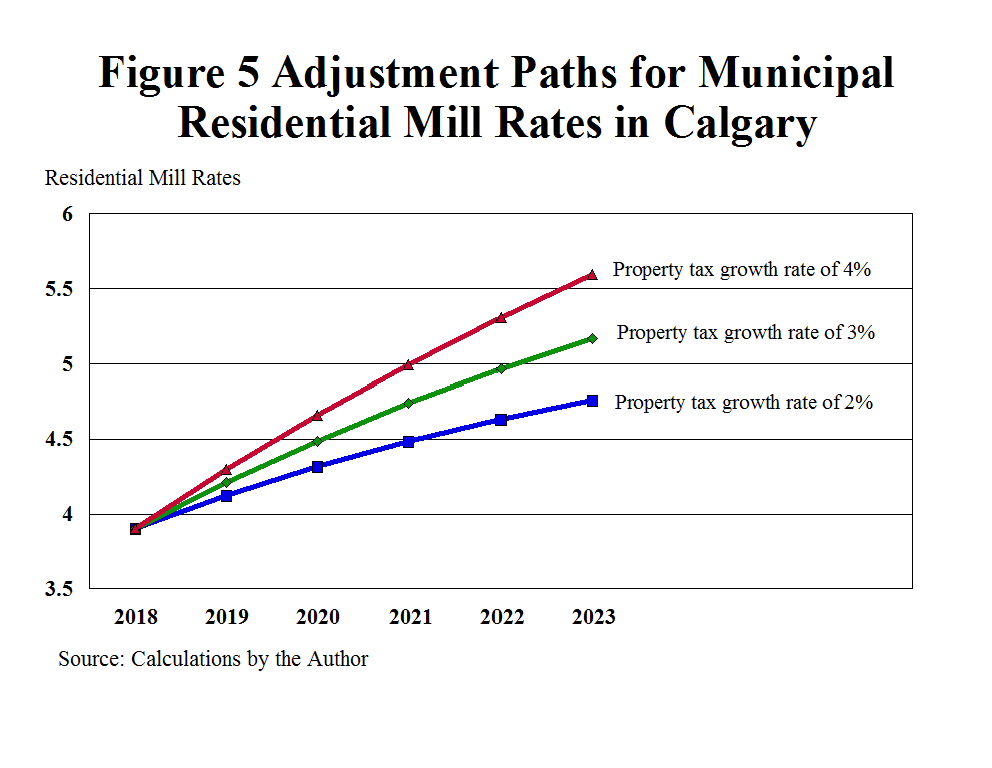

A gradual rebalancing of the property tax burden away from businesses to homeowners should be part of the City’s long term fiscal plan. While there would be many alternative adjustment paths, here we will outline one scenario that puts the magnitude of the required changes in the residential mill rate in perspective. Suppose the City maintained the 2018 non-residential property tax rate at 15.3234 mills in the future. The required residential mill rate would then depend on the rate of change in residential and non-residential assessment and how rapidly the total property tax revenues have to increase to finance the City’s expenditures. For illustrative purposes, suppose current property market trends continue with total residential assessment increasing by 4 per cent a year and non-residential assessments declining by 4 per cent a year (a rather pessimistic scenario).

Figure 5 shows the implied residential mill rates up to 2023 if total property tax revenues grow at 2, 3, or 4 percent a year. This scenario shows how important some combination of expenditure restraints and accessing other sources of revenues, such as increasing user fees, is for moderating the rate of increase in property taxes on homeowners.

Conclusion

No one likes paying higher taxes, but there is a strong case for rebalancing the property tax burden from the businesses to homeowners if Calgary wants to maintain its status as a business friendly city with a vibrant entrepreneurial culture. It is time for the Calgarians and their elected officials to face up to the fiscal challenge of reducing reliance on taxing businesses to fund the public services that make Calgary a great place to live and work.

References

City of Calgary. 2018. “Chief Financial Officer’s Report to the Priorities and Finance Committee”. September. https://pub-calgary.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=66729

Dahlby, Bev and Kevin Hassett. 2018. “The Economic Effects of the Corporate Tax: A Review of the Recent Literature.” in Reforming the Corporate Income Tax in a Changing World, Canadian Tax Foundation, May 20, pp. 45-86.

Found, Adam and Peter Tomlinson. 2017. “Business Tax Burdens in Canada’s Major Cities: The 2017 Report Card” C.D. Howe Institute. E-brief 269. December.

Mintz, Jack and Tom Roberts. 2006. “Running on Empty: A Proposal to Improve City Finances” C.D. Howe Institute Commentary, No. 226 February.

Potkins, Megan. 2018. “City Counld Spend Twice as Much in 2019 to Alleviate Tax Burden Caused by Empty Office Towers” Calgary Herald, October 26.

Varcoe, Chris. 2018a. “City Council Faces ‘Come-to-Jesus Moment’ As Shrinking Value of Downtown Towers Leaves Huge Tax Gap” Calgary Herald, October 23.

Varcoe, Chris. 2018b. “We’re No. 1. Calgary Sees Highest Jump in Commercial Property Tax Rates Among Canadian Cities” Calgary Herald, October 25.

Varcoe, Chris. 2018c. “Looming Tax Shift Could Be Extra Scary for Calgary Businesses” Calgary Herald, October 31.